The Father of Scientific Management...for Good and Bad

February 1, 2008Comments

Frederick Winslow Taylor. He’s the seed that spawned every manufacturing organizational, productivity and labor plan and theory in use today, and in his day he was a lightning rod in the battle of classes.

Born in 1865, Taylor obsessively pursued any to make anything better. For example, at age 12, convinced that sleeping on his back caused nightmares, he developed a harness to keep from rolling over in bed.

As chief engineer at a steel company, Taylor watched workers carefully, and measured product output. His goal: Find the most efficient to perform specific tasks. At the end of the 19th century, manufacturing managers sought increased productivity chiefly via incentive wages—produce more, get paid more.

Taylor saw incentive pay as one aspect of productivity, to be paired with efficient tasks that could be learned by the workforce. This approach was termed “scientific management.” His time studies resulted in production quotas, where workers would make more money by reaching their daily goals—those that didn’t received a lower wage, got transferred or were fired.

Naturally, Taylor’s wage plan, based on his time studies, raised productivity. But the increased production speed and improved process accuracy led to drastic job cuts. At one company, Taylor, as a consulting engineer, recommended changes that brought huge improvement, but reduced employee rolls from 120 to 35. In 1901, as consultant to the forerunner of Bethlehem Steel, he analyzed daily output and costs. With his assistance, the company installed modern production-planning and accounting systems. His work helped double production and bring a multitude of cost savings. One major consequence of Taylor’s efforts: The number of yard workers was cut from 500 to 140. Even management became upset. He was fired from the Bethlehem assignment because the newly unemployed could no longer afford to rent housing owned by company managers.

One opponent of Taylor’s principles, Upton Sinclair, took issue with an article Taylor authored in 1911 describing how “workingmen” loading 12.5 tons of pig iron and making $1.15 per day were induced to load 47 tons instead, earning them $1.85 per day.

“Thus it appears that (Taylor) gave about a 61-percent increase in wages, and got a 362-percent increase in work,” wrote Sinclair, commenting that the percentage ratio was unfair. “He tells us we have no need to worry because seven men out of eight are turned out of their jobs, because there are plenty of jobs for them in other parts of the plant.” Sinclair predicted massive job losses followed by a worker revolution.

Taylor responded that Sinclair focused on the employee and employer while ignoring the most important party, the consumers, “who ultimately pay both the wages of the workmen and the profits of the employers.” Taylor reasoned that “in the past 100 years, the greatest factor tending toward increasing the output and thereby the prosperity of the civilized world, has been the introduction of machinery to replace hand labor.”

Many saw Taylor essentially as a condescending jerk, an opinion cemented with quotes like this, where he discusses the need for a higher-producing worker to get a raise, but not too much of a raise: “…this increase in wages tends to make workingmen better in every …they live better, begin to save money, become more sober, and work more steadily.” But with too high of a wage, “many of them will work irregularly and tend to become more or less shiftless, extravagant and dissipated. Our experiments showed, in other words, that for their own best interest it does not go for most men to get rich too fast.”

There you have it, the father of scientific management. His ideas helped shape American productivity, but he might have benefitted from a course in How to Win Friends and Influence People.

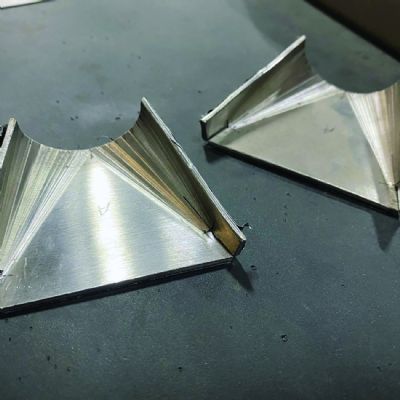

Technologies: Bending

Comments

Must be logged in to post a comment. Sign in or Create an Account

There are no comments posted. Bending

BendingCreative Approaches to Common Press Brake Challenges, Part 1...

Justin Talianek Tuesday, April 30, 2024