“Good point, but for thinner materials, short circuit probably makes more sense. Besides, we started out talking about control,” offered Nathan Lott, Esab applications engineer. “What about the additional pulsing controls that can help operators achieve desired results, such as reducing spatter?”

Crisis in Progress?

Here’s where the discussion went sideways.

“If operators these days understood basics, spatter would be less of an issue,” countered Ginder. “Just because someone can pull a GMAW gun trigger doesn’t make him a welder.”

|

| Operators need to ask fundamental questions such as, “Why are gun angle and travel direction so critical?” |

The group agreed that the technical-education crisis goes beyond the need for more skilled tradespeople, with many students overlooking the need to equip themselves with fundamental skills, knowledge and inquiring minds.

“If you can find a problem solver, a thinker and a researcher, you’ve got the making of a good welder,” said Lipko. “The problem is, I see kids who have trouble finding 15⁄16 in. on a tape measure or figuring out the diameter of a pipe.”

The issue extends to industry as well, especially for companies that rely on institutional knowledge that creates we’ve-always-done-it-this-way mentalities. Examples cited by the group include a structural-steel shop where 90 percent of the operators pushed a gas-shielded flux-cored wire when welding in the flat position. Employees there never wondered if dragging the gun would reduce slag inclusions. Another example includes choosing a smaller wire diameter because it’s easier to weld with (because of its slower deposition rates), yet requires excessive manipulation to achieve good sidewall fusion. Using a larger wire that catches both sides of the joint with no manipulation could produce more consistent results. Welding faster with a larger wire also reduces heat input.

“Good welds result when operators understand gun mechanics and welding principles,” added Grinder. “But since you asked my opinion, basic short-circuit GMAW can be a good choice for thin steel-fabrication. That is, when operators understand the fundamentals.”

|

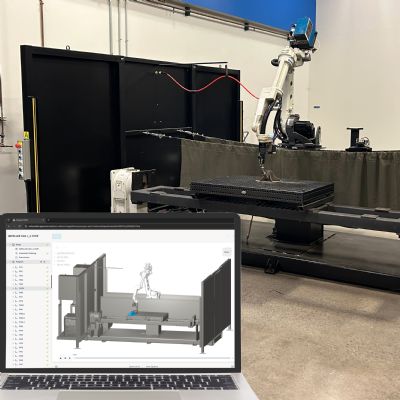

| With a shortage of skilled welders, companies benefit from advanced GMAW systems with preset programs for welding with various processes, synergic controls and smart GMAW functions. |

Delving deeper, the application engineers noted that, beyond personal preferences, too many operators don’t know why they should push or drag the gun in a given solid-wire application, nor do they ask why gun angle is so critical. For the record:- Pushing directs arc force away from the puddle to produce a wider and flatter bead with less penetration.

- Dragging directs arc force at the puddle to produce deeper penetration and a narrower bead with more buildup.

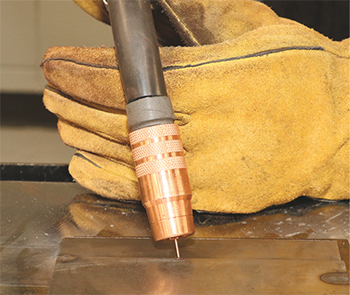

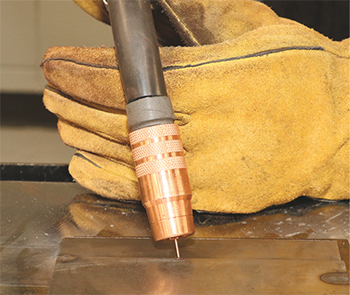

- Achieving a gun angle (or angle of travel) of 5 to 15 deg. from perpendicular is required in most situations.

- Seeking recommendations for specific applications from filler-metal manufacturers is better than seeking advice from online bulletin boards that may contain inaccuracies.

“The problem is that people practice with poor mechanics, and practicing wrong isn’t going to make you a better welder,” said Lott. “They use too much gun angle and don’t realize it increases arc instability and spatter, much less realize they’re losing penetration.”

Wanted: More Questions

In summary, operators who know the whys of GMAW have a host of controls besides wire-feed speed and voltage. Unfortunately, the industry has a shortage of such operators, and welding businesses need to deliver results today. Enter preset programs and functions that automatically adjust and compensate for some GMAW variables. These are good things, right? Yes, but…

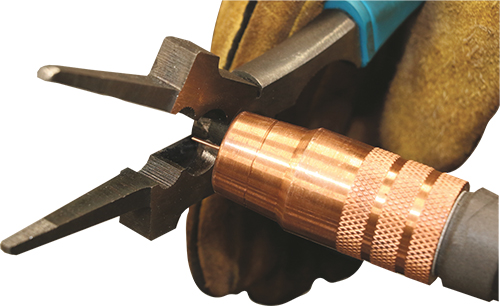

“Not enough people know why factors such as electrical stickout and contact-tip-to-work distance influence arc stability, wire melt-off rate, penetration and weld-bead shape,” said Ginder. “Yes, preset programs, synergic controls and smart GMAW functions help compensate, enabling operators with less skill to obtain good results. But we’d be happier if more people asked: ‘Why do they help?’” MF

Author’s note: The article, Optimize Aluminum Welding Performance, in the May 2015 issue of MetalForming, discusses pulsed GMAW controls in detail and is worth reviewing: metalformingmagazine.com/magazine/article/?/2015/5/1/Optimize_Aluminum-Welding_Performance.

See also: ESAB Welding & Cutting

Technologies: Welding and Joining