Reverse Tonnage

Reverse-unloading forces introduce large downward accelerations to the upper-die half when suddenly released. These forces essentially work to separate the upper die from the bottom of the ram on every stroke. If the die-clamping system has insufficient clamping force, the upper-die half could separate from the bottom of the ram on each stroke, causing fatigue to the upper-die mounting fasteners.

Reverse-unloading forces introduce large downward accelerations to the upper-die half when suddenly released. These forces essentially work to separate the upper die from the bottom of the ram on every stroke. If the die-clamping system has insufficient clamping force, the upper-die half could separate from the bottom of the ram on each stroke, causing fatigue to the upper-die mounting fasteners.

Uncontrolled, high reverse loads also can fatigue the press structure. Fatigue-related cracks can propagate in the ram, drive linkage, crown, uprights and bed, eventually producing a sudden and unexpected catastrophic failure.

Reverse loads also associate with product-quality issues due to premature wear or breakage of punches and dies.

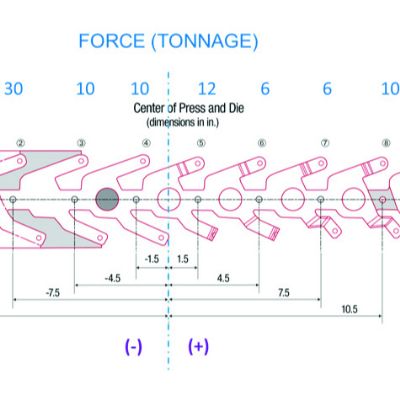

Because the press can withstand more stress in compression than tension, forward-tonnage capacity measures much higher than reverse-tonnage capacity. A press equipped with a tonnage monitor can display reverse loads. Unfortunately, the loads displayed are small in relationship to the forward capacity of the press and often—mistakenly—are deemed inconsequential.

Most press designs feature approximately 10% of their maximum-rated forward load in reverse tonnage, with some exceptions. Review your machine’s operating manual for specific capacities or consult with the press builder.

Assuming, for example, that a 400-ton press has 10% reverse-tonnage capacity, it should not exceed 40 tons of reverse load. When the tonnage monitor displays a forward load close to or exceeding the 400-ton capacity of the press, operators and others may tend to respond very quickly to safeguard the press. The same urgency and immediate response also should occur when reverse loads approach or exceed 40 tons—immediately stop the process.

Monitor reverse tonnage throughout the production run, not only during setup. A newly sharpened blanking die may generate 250 tons of forward tonnage and 35 tons of reverse tonnage. While both forces fall within the capacity of the 400-ton press, as the die wears during production, forward tonnage will creep upward. Given a blank of acceptable quality, the die can run even if the forward tonnage exceeds 300 tons, as this force resides well within the rated capacity of the press. On the other hand, reverse tonnage could exceed the 40-ton reverse-tonnage capacity of the press if not monitored regularly.

Signs of Excessive Reverse Tonnage

Press technicians should understand well the symptoms of excessive reverse tonnage.

The first indicator: loudness. If consistently hearing a “boom-boom, boom-boom” sound during a blanking operation, ask yourself, “What caused that second boom?” It likely originated in the press structure as it released built-up stresses and the clearances in the drivetrain reverse from one side of the connections to the other abruptly and forcefully. The impact is powerful enough to be heard. Unfortunately, few may understand this noise…it’s the press crying out for help.

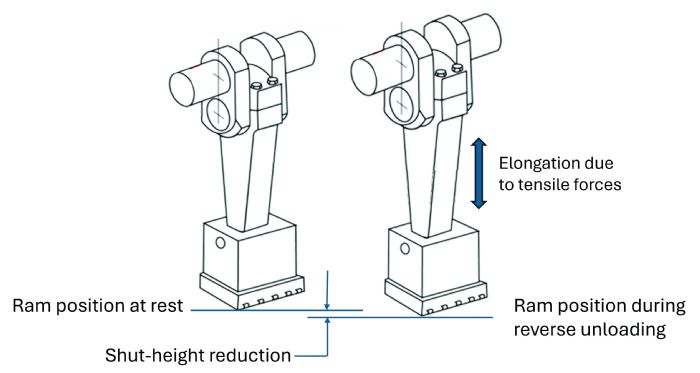

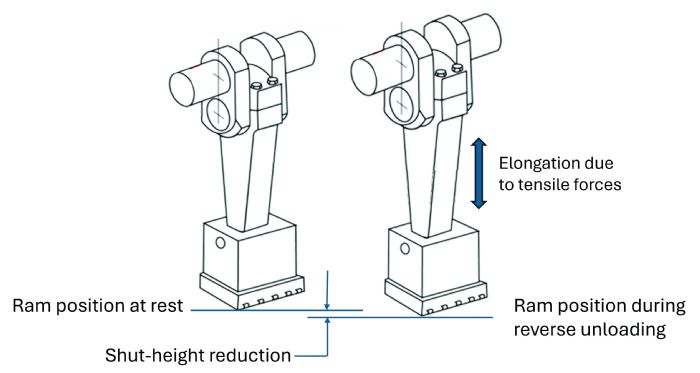

Also, look for impressions of the set block in the upper-die shoe caused by a reduction in die shut height when the pitman connection elongates due to excessive tensile forces during unloading (Fig. 2).

Other symptoms include loose bolts, pneumatic lines and hydraulic hoses; electrical malfunctions due to loosened connections; premature punch and die wear; and foundation issues. Operators and technicians may feel symptoms as well: fatigue in their feet, ankles, knees and hips. Back problems sometimes arise.

What to Do?

Press technicians should closely monitor reverse tonnage on all jobs capable of producing high levels of reverse unloading. Report the issues to management or toolroom personnel. The toolroom can add shear to the die cavity or stagger the punch-entry timing to reduce forward and reverse tonnage. Another option: adding counterpressure inside of the die using nitrogen or hydraulic cylinders.

If available, consider mounting shock dampers to the press bed. If the press utilizes servo-drive technology, slow the ram near the bottom of the stroke to reduce impact with the work material. If these options are not available, move the process to another press with greater reverse-tonnage capacity.

The worst thing a press technician can do regarding excessive reverse tonnage: nothing. MF

Industry-Related Terms: Bed,

Blank,

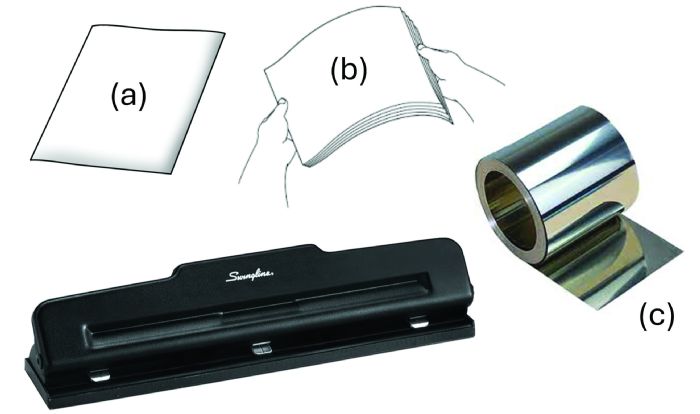

Blanking,

Die,

Lines,

Ram,

Run,

Shut Height,

Stroke,

Tensile Strength,

Thickness,

Blanking DieView Glossary of Metalforming Terms Technologies: Tooling

Stampers must anticipate the magnitude of these forces during the die-design process so that engineers may assign presses properly and incorporate countermeasures that safeguard the die and the press. Press technicians should understand the cause and effects of these unloading forces and know the implemented countermeasures to prevent unintentionally negating their benefits.

Stampers must anticipate the magnitude of these forces during the die-design process so that engineers may assign presses properly and incorporate countermeasures that safeguard the die and the press. Press technicians should understand the cause and effects of these unloading forces and know the implemented countermeasures to prevent unintentionally negating their benefits.

Reverse-unloading forces introduce large downward accelerations to the upper-die half when suddenly released. These forces essentially work to separate the upper die from the bottom of the ram on every stroke. If the die-clamping system has insufficient clamping force, the upper-die half could separate from the bottom of the ram on each stroke, causing fatigue to the upper-die mounting fasteners.

Reverse-unloading forces introduce large downward accelerations to the upper-die half when suddenly released. These forces essentially work to separate the upper die from the bottom of the ram on every stroke. If the die-clamping system has insufficient clamping force, the upper-die half could separate from the bottom of the ram on each stroke, causing fatigue to the upper-die mounting fasteners.

Webinar

Webinar