New Coating Prevents Punch Ends from Ripping Off

March 1, 2010Comments

Longer punch life keeps the presses running at this Connecticut automotive-parts supplier.

In 1838, C. Cowles & Company opened to provide lanterns for the thriving carriage trade in New Haven, CT. Today, its subsidiary, Cowles Stamping Inc., also in New Haven, carries the transportation torch as a Tier Two automotive supplier. In fact, it was one of this country’s original suppliers to the OEM automotive industry; it also supplies complex metal stampings and subassemblies to the bearing, seals and shields industries as well as other nonautomotive businesses.

|

| A change in tool coatings at Cowles Stamping increased punch life from 3000 to 16,000 hits between sharpenings when stamping HSLA-steel automotive parts. |

Early in 2008, the firm found that when stamping parts for one automotive customer, its punches were breaking after only a few thousand hits. The problem: the punches were getting caught in the material. The solution: a switch to a new punch coating, which brought significantly longer punch life and increased productivity.

Broken Punches Stalled Job Runs

In its 80,000-sq.-ft. manufacturing facility, Cowles employs mechanical presses from 35 to 250 tons to provide precision small- and medium-sized stampings from material 0.01 to 0.25 in. thick. Other inhouse capabilities include welding and assembly, tapping (in die and secondary-operation), plating, heat treating, powder coating and finishing. Up front, Cowles leverages its engineering and rapid-prototyping expertise to help customers with product development. It also staffs a full-service toolroom to build smaller dies and maintain dies in stock.

On a couple of jobs, including the automotive stamping referenced above, tool maintenance had become quite a burden.

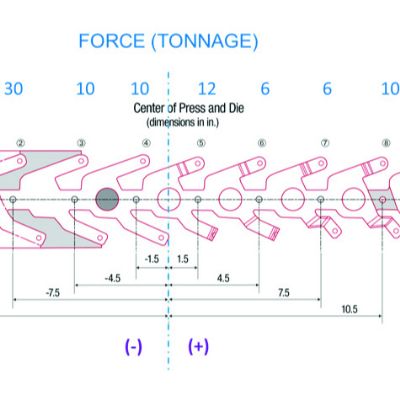

“After 3000 pieces, the punches—coated with a titanium-nitride product—actually pulled apart,” explains Cowles engineering manager Whyn Pelkey, describing difficulties experienced on an automotive part stamped on a progressive die in a 250-ton press at 35 strokes/min.

“The punches could not be sharpened due to the punch breakage,” recalls Steven Couture, Cowles manufacturing design engineer, noting that these types of punches, used to pierce holes, “are not conventionally restrained, but are taper-cut and then pressed into a holder.”